Motivation

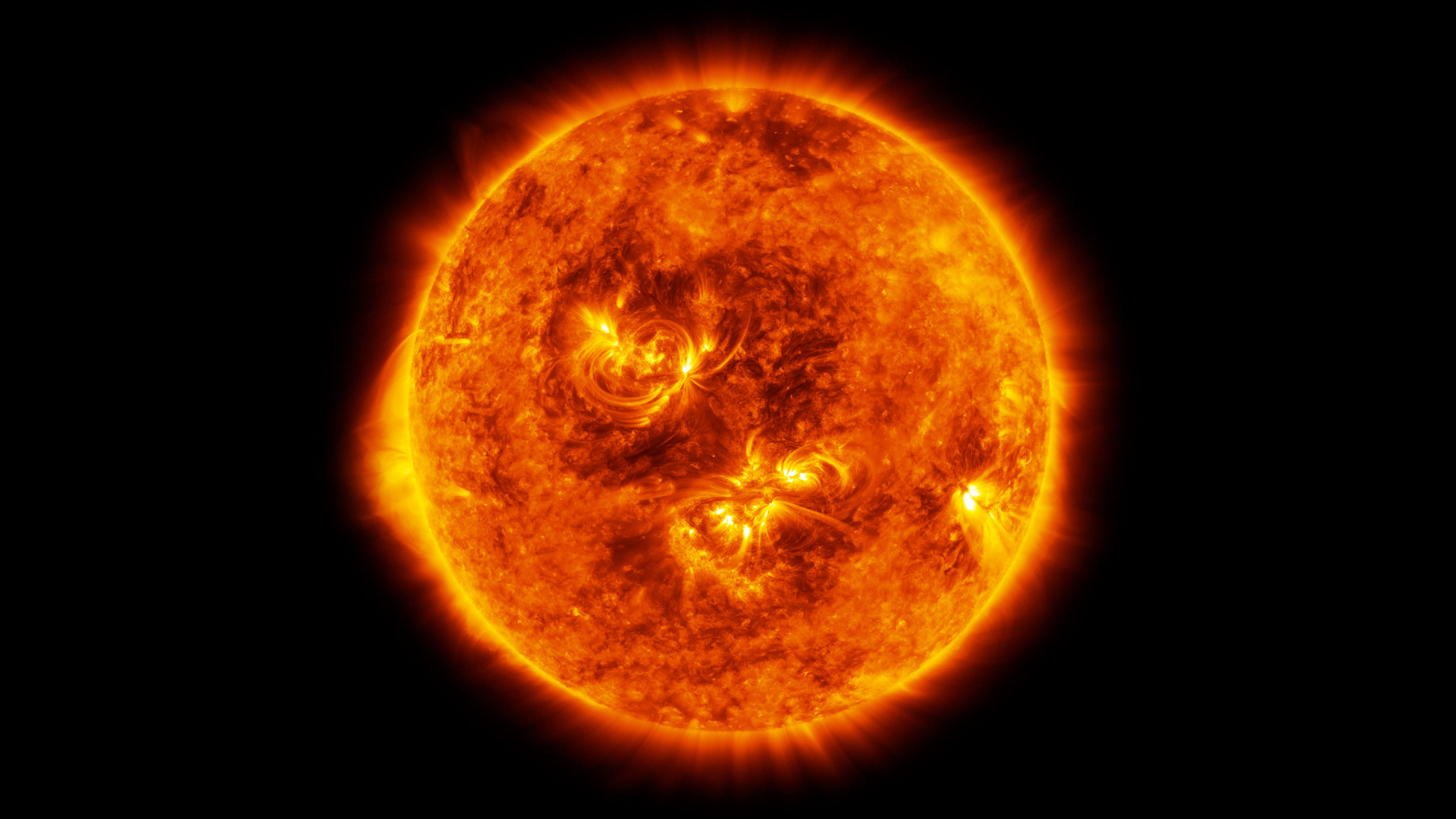

Nuclear fusion, the process powering the sun and stars, has long been touted as a silver bullet to humanity’s energy crisis, with the potential to also accelerate human development, reduce energy resource conflicts and tackle global warming. However, it has remained elusive for decades as a commercially feasible solution due to long-standing challenges and concerns, including whether it will ever be a practically viable and competitive source of commercial energy.

Leaving aside the question of how, if we can implement a commercially feasible nuclear fusion reactor within the confines of the physics we know today, it would accelerate human development. The main reasoning for that line of thinking is attributed to the abundance of the fuel and the enormous energy density advantage over other sources of energy.

More

The fuel in question can alter this reasoning. Currently, the leading candidate is the Deuterium and Tritium combination (hydrogen isotopes with 2 and 3 neutrons in the atomic nucleus, respectively), for which Tritium seems to be rare and challenging to source. Even so, the reactor design proposals often incorporate a tritium breeding design from a more commonly available element (the most common scheme involving what’s essentially nuclear fission of a Lithium isotope using the neutron particle produced in the Deuterium-Tritium reaction). It is also thought that technology will evolve to other reactions later, which reduces this dependency, but that involves more uncertainty in forecasts.

The energy density advantage mostly boils down to Einstein’s famous (E=mc^2) mass-energy equivalence, and since the mass “lost” is relatively high in the candidate nuclear fusion reactors, they are often many orders of magnitude more energy dense as a fuel compared to chemical reactions. For practical purposes, the density should take into consideration the entire reactor, which may be lower, but the thought is that the potential entitlement is attractive to make it a worthwhile pursuit.

We’ll cover these topics in detail in later sections.

The Author's take on it:

Some of the scepticism is driven by the fact that optimism in the past failed to materialise, leading to the cliche declaration, "Nuclear Fusion is always x years away". I appreciate this, and it is a matter of fact that many of the predictions about nuclear fusion in the past were, in hindsight, hopelessly unrealistic. There are also numerous technological, commercial and political challenges today, some of which seem challenging enough for some veterans in the field to conclude that it's a lost cause.

It may very well be a lost cause, but I'm not convinced yet that "Argument from Authority" settles the matter. The field of nuclear science has witnessed this before, with Rutherford and Millikan, pioneers in the field, who went on to express harsh scepticism about atomic energy ever being harnessed by humans. They were in good company, as so did Einstein. It did not take long for them to be proven wrong, but that was likely due to geopolitical events at the time (the Manhattan project being an outlier compared to the natural evolution of technology in peaceful times). Ultimately, it comes down to a combination of potential gains and anticipated challenges. It's not rational to pursue something that goes against the known laws of physics, but fusion reactors are far from that, in my opinion. It is also clear that that is a low bar for narrowing down to worthwhile causes, and it's a lot more challenging than one would conclude after a brief glance at the theoretical entitlement. The applied physics and engineering challenges are amongst the greatest there is.

So is it worth the effort? The amount of energy that humanity can

harness seems to be an indicator of our technological advancement, and a

proxy indicator of human development.

In my opinion, if there is a technological “silver bullet” that can

potentially help promote peace, bring about poverty reduction, tackle

global warming, catalyse space exploration and enable technologies

unthinkable today, it has got to be Nuclear Fusion.

More

The advantages I mention are based on how there's an indirect influence:

- Promotion of peace by mitigating energy resource conflict, which usually influences most conflicts between sovereign entities.

- Bring about poverty reduction through better energy equity, which in turn can improve living conditions.

- Tackle global warming through fossil fuel replacement with lower energy storage demands, better energy density, on-demand generation and control that most means of renewable energy generation.

- Enable technologies that are not feasible today, largely because the majority of the energy sources involve limited release of energy released from chemical reactions. Scaling up is possible, but only until you hit the energy density wall.

As far as scepticism goes, the one that I consider to be the litmus test for our evaluation is that by Lawrence Lidsky, as many of the arguments he made in the 80s are still valid today, and it provides some insight into what the expectations of the nuclear scientists in the day were.

- L. Lidsky, “The Trouble With Fusion,” MIT Technology Review, October 1983

- MIT News, “Retired MIT Professor Lidsky dies; questioned fusion power research,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 5 March 2002.

Some references to scepticism regarding the feasibility of humans extracting energy from nuclear reactions, expressed by Rutherford, Millikan and Einstein, are also provided. It's worth noting that some of this could be a disingenuous statement made deliberately to avert the militarisation of such technology. If that were the intent, it was unsuccessful, and I suspect that they would be for harnessing the energy for civilian utility over militarisation.

- R. Millikan, “Available Energy,” Science, vol. 68, no. 1761, pp. 279-84, 1928.

- S. Weart and M. Philips, “History of Physics / Readings from Physics Today. Number Two,” Associated Press, 1985.

- A. Moszkowski and H. Brose, Einstein the Searcher: His Work Explained from Dialogues with Einstein, New York: Routledge, 1922.